Authentic Images of Shakespeare*

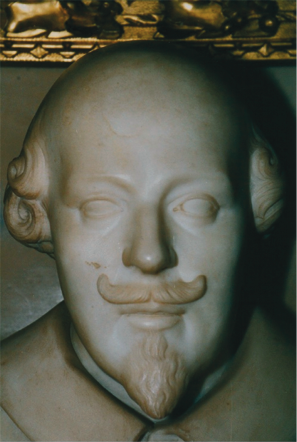

Collaborating with scientists and scholars from various other disciplines, including experts from the German Federal Bureau of Criminal Investigation (BKA=CID or FBI), Professors of Medicine, physicists, 3D imaging engineers, archivists and an expert on old masters, Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel succeeded in proving the identity and authenticity of four likenesses of William Shakespeare, which had formerly been questioned in Shakespeare scholarship. These are: the Chandos portrait (National Portrait Gallery, London), the Flower portrait (Royal Shakespeare Company Collection, Stratford-upon-Avon), the Davenant bust (Garrick Club, London) and the Darmstadt Shakespeare death mask (Hesse Land and University Library, Darmstadt, Germany).

The basis for comparison consisted of the Droeshout engraving of Shakespeare in the First Folio Edition of his Plays (1623), confirmed by dramatist Ben Jonson, and the funerary bust of Shakespeare in the Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon (1616/1617).

In January 1995, to establish the identity of the portrayed individual, the author contacted the President of the BKA to request his support. He accepted her request and the BKA experts Reinhardt Altmann, Jörg Ballerstaedt and Dietrich Neumann conducted two separate testing procedures: the Conventional Comparison of Images used in criminal investigations and the so-called Trick Image Differentiation Technique (photomontage of electronic images). In the image comparison, seventeen matching morphological features in the Droeshout engraving, Chandos portrait and Flower portrait were found. This constituted the proof that all three likenesses portray the same person.

Application of the Trick Image Differentiation Technique to the Chandos portrait and Droeshout engraving, Droeshout engraving and Flower portrait, death mask and funerary bust as well as the death mask and Davenant bust, produced astonishing harmony and agreements in all cases, such that the identity of the reproduced persons could be clearly and convincingly established.

The two expert reports by Reinhardt Altmanns from 3 May 1995 and 6 July 1998 produced proof that the portraits examined depicted one and the same person.

That this person must be William Shakespeare results from the fact that the Droeshout engraving reproduces the facial features of the poet authentically. This was confirmed in verses by a prominent contemporary of Shakespeare’s which appeared – together with the portrait of the author -- in the First Folio Edition of Shakespeare’s play in 1623. The author of these verses is the English poet and playwright Ben Jonson (1572-1637), who knew William Shakespeare very well.

Thus, the theretofore open identity question regarding the Chandos portrait, the Flower portrait, the Darmstadt Shakespeare death mask, and also the Davenant bust, was solved.

The findings of the BKA expert report of 3 May 1995 also led to the conclusion that the sculptor of the funerary bust, Gheerart Janssen d. J., must have used the Darmstadt Shakespeare death mask as his model.

In the Chandos and Flower portraits as well as the death mask Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel discovered signs of sickness which several Professors of Medicine from different specialized areas assess in expert reports.

The swelling on the left upper eyelid and the left temple on the Chandos and the Flower portraits, which is also reproduced on the Droeshout engraving was diagnosed by ophthalmologist Prof. Walter Lerche as the Mikulicz Syndrome (see medical appraisal of 11 April 1995). Lerche considered the severe swelling on this side might be a lymphoma. The swelling on the left caruncle he interpreted as a “fine caruncular tumour”. It was left out of the Droeshout engraving or was but vaguely indicated. Thus the chronology of the Droeshout engraving and Flower portrait – theretofore disputed – could also be settled: if the painter of the Flower portrait had worked on the basis of the Droeshout engraving, he would not have been able to detect the caruncular tumour and would have had to invent it, something that can be ruled out. The Droeshout engraver must have used the Flower portrait as his model and taken the liberty of merely hinting at the caruncular swelling.

At the beginning of 1996 the author noticed a sign of disease on the forehead of the restored Flower portrait and the death mask, which she also asked medical specialists to appraise.

In the opinion of pathologist Prof. Hans Helmut Jansen this was a (benign) “bone tumour” (see medical appraisal of 28 February 1996). In connection with the pathological symptoms diagnosed by Prof. Lerche, dermatologist Prof. Jost Metz interpreted the sign of disease as a “chronicly inflammable infiltration” which was most likely a “chronic, annular skin sarcoidosis” (see medical appraisal of 23 January 1996). This creeping systemic disease, which can affect any organ, leads to death normally after many years in Prof. Metz’s view. It might also have been the cause of Shakespeare‘s death.

The swelling of the upper left eyelid also appears on the death mask, although in a different form. This can be explained by (1) the backwards dorsal position of the deceased, (2) the shrinking of the tissue through the loss of blood pressure, (3) the fact that the eyelid is closed, as well as (4) the pressure of the plaster layer which causes a distribution of the tissue mass. The medical expert on death masks, Prof. Michael Hertl, confirmed the explanations of the author in his expert report of 15 August 1997, and spoke of a “considerable reduction” post mortem. He added that “the eyes and the other contents of the eye sockets” in the course of a long, consuming disease process, “were already very sunken before dying and death.”

|

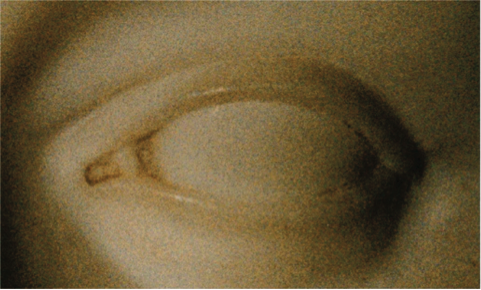

The strikingly protruding, distorted left eye of the death mask. |

Among other things, in his thorough medical appraisal Prof. Hertl came to this conclusion: “The Damstadt mask is indisputably the original mask. From a biological standpoint this is emphasized by the fact that as the hardened plaster was pulled away countless tiny hairs came away from the skin of the face, as well as some hairs from the eyebrows, eyelashes, and beard. They were not artificially introduced with fraudulent intent as [Ernst] Benkard asserts in his unfounded (mis)judgement on the mask.” [Das ewige Antlitz. Eine Samlung von Death Masken. Berlin, 1929, S. 71]

In August 1996 Dr.-Ing. Christoph Hummel, in the presence of the author and the former Headmaster of the Grammar School in Stratford-upon-Avon, George Shiers, noticed three swellings in the nasal corner of the left eye on an older marble copy of the funerary bust. The copy is in the Elizabethan stately home Charlecote Park in Warwickshire and shows that the prominent swelling must also have been found on the funerary bust in Stratford.

|

Charlecote Park near Stratford-upon-Avon. The 16th century stately home of the Lucy family. William Shakespeare is said to have poached on Sir Thomas Lucy’s estate. |

This also attests to the so-called Hunt Portrait in Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, which was painted on the basis of the funerary bust.

The swelling in the nasal corner of the left eye of the funerary bust must have been removed (presumably by mistake) in the 19th century, in the course of removal of a coat of white paint.

On request of the author, Dr.-Ing. Rolf Dieter Düppe of the Institute for Photogrammetry and Cartography at the Technical University of Darmstadt took a photogrammetric measurement of this area of the death mask. This showed – under an almond-shaped opening – the crater-like remains of a trilobate swelling.

In his expert assessment of 15 August 1997 Prof. Hertl quoted from Düppe’s report: “With the most powerful enlargement and spatial evaluation (stereoscope) I saw a hollow space surrounded by a wall of highly porous and granular appearance, on the uneven floor of which two smaller and one larger craterlike formations were to be recognised. One has the impression here that something has crumbled out by itself or was removed by ‘cleaning work’. The – in terms of extent – larger ruin of a protuberance is the one lying closest to the iris.”

The results of this investigation provided additional and clinching evidence of the authenticity of the Darmstadt Shakespeare death mask. They also proved that the sculptor Gheeraert Janssen the Younger must have used the mask as his model for Shakespeare’s funerary bust in 1616/17. This had already been suggested by at 19th-century painter.

On an infrared photograph of the Chandos portrait, taken before 1969, an incipient trilobate swelling is already visible in the nasal corner of the left eye. Later this caruncle tumour must have grown vigorously.

|

| Detail of an infrared image of the Chandos Portrait: nasal corner of left eye with an incipient trilobate swelling. |

It appears that such a sign of illness was visible in the same location of the Davenant bust as well, but must have been removed. In his expert opinion of 11 September 1998 the medical specialist Professor Hertl wrote: “In the nasal corner of the left eye [of the Davenant bust] there is a space-occupying lesion, a lumpy thickening of tissue … as well as an indication of an eyelid margin deviation such as a space-occupying process induces – a picture identical in principle to earlier findings.”

It can also reasonably be assumed that a significantly protruding swelling was originally extant on the upper left eyelid of the Davenant bust as well, a swelling which must have been scraped off later.

These changes may have been made by William Clift (1775-1849), the first Curator of the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, London, who concealed his discovery of the bust for many years. He confided in his diary that by night he had removed the coats of paint that had been applied as conservation. In the process he apparently tried to remove the swellings which he found disturbing. Clear scratch marks, which probably date back to Clift, are also visible on the forehead of the Davenant bust, and exactly in the place of an enlargement, which according to Prof. Hertl corresponds in type and size to those on the death mask and restored Flower portrait. In 1998 the mathematician and physicist Prof. Nico Gray of the University of Manchester took very time-consuming photogrammetric measurements of the Davenant bust in the London Garrick Club. The author is grateful to him for the valuable special high-resolution images, which made it possible for the first time to bring to light further details of Shakespeare’s face and to document photographically convincing traces of the signs of disease the poet suffered from.

Formerly the Davenant bust was considered the work of the French sculptor Louis-Franςois Roubiliac (1695-1762). However, the “striking harmony between the facial areas presented and between the morphological characteristics“, which BKA expert Reinhardt Altmann established through application of his tried and proven testing techniques to the Davenant bust, Chandos portrait, Flower portrait and death mask, but also among the Davenant bust, Droeshout engraving and funerary bust, “leads to the inescapable conclusion,” as he wrote in his expert appraisal of 6 July 1998, “that one [and the same] person is represented here.”

Altmann’s results were confirmed by a further measuring procedure. In November 2004 geodetic specialist Dipl.-Ing. Thorsten Terboven, Sales and Application Engineer 3D (Germany), carried out the measurements on the death mask with a 3D Laserscanner VI-910 made available by the firm of Konica Minolta Photo Imaging Europe, in the Hesse Land and University Library in Darmstadt. In February 2005, with a Laserscanner of the same type, David Lowry, Application Engineer 3D (United Kingdom), took 3D measurements of the Davenant bust in the London Garrick Club.

The images produced in this procedure were evaluated by Prof. Dr. Dipl.-Phys. Bernd Kober, Director of the Institute for Radiation. Kober stressed that the agreement between faces could be determined by the comparison of the “distance between the edges of certain bones,” for example, the “upper edge of the orbit (eye socket)” and the “point of the chin.” In his expert report of 30 June 2005 Kober confirmed in summary that the death mask and Davenant bust represent “the same person.”

These findings, and the fact that the Davenant bust displays signs of disease which are also extant in the same location in the Chandos portrait, the Flower portrait and the death mask, show that the Davenant bust is also a true-to-life image of William Shakespeare.

Due to the precision with which the Davenant bust reproduces the facial features of the poet, it must have been done with a living model and life mask. The medical expert Prof. Hertl confirmed this in his appraisal of 11 September 1998.

On the basis of the new research findings that the author has presented, the history of the Davenant bust can be traced back to its first known owner, the dramatist William Davenant (1606-1668) (cf. The True Face of William Shakespeare. The Poet’s Death Mask and Likenesses from Three Periods of His Life, S. 82-87). Davenant was Shakespeare’s godson and most probably also his natural son. The proof of identity and authenticity presented for the Davenant bust definitively exclude the French sculptor Roubiliac as author.

Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel is of the view that the young Nicholas Stone (1586-1647), who had returned to London from Amsterdam in 1613, may be the creator of the Davenant bust (cf. The True Face of William Shakespeare, S. 88-89). Stone, who in the course of the 17th century was to become the most celebrated sculptor in England, was a student of the most important Dutch sculptor and master builder, Hendrik de Keyser (1565-1621), who produced the models for his figures in terracotta.

Stylistically the Davenant bust resembles de Keyser’s true-to-life bust, “Bust of a Man” (“Borstbeeld van een man”) from 1606.

|

| Hendrik de Keyser, “Bust of a Man”, 1606 https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/explore-the-collection/works-of-art/terracotta/objects#/BK-NM-4191,12 |

There are two copies of the Davenant bust that its (co)owner, Richard Owen (1804-1892), Anatomy Professor at the British Museum and son-in-law of the man who found it, William Clift, had made before he sold the original to the Duke of Devonshire. One of the copies went to Stratford, where it is still to be found in the Royal Shakespeare Collection, the other remained in the British Museum. There it was wrongly classified as part of Roubiliac’s estate. In 1855 the Duke of Devonshire gave the original to the London Garrick Club, where it is kept today.

Summary**

All of the images investigated reproduce Shakespeare’s appearance authentically. The two paintings, Chandos and Flower, were painted from life and are faithful portraits of the poet. The Davenant bust too is an authentic image created during Shakespeare‘s lifetime, which must have been based on a life mask. It meticulously depicts all the characteristics of Shakespeare’s face, including even the finest detail. The death mask is also authentic and an exact likeness of Shakespeare. It was taken soon after the poet’s death and served as the model for the sculptor of the funerary bust, which accurately copies the death mask on a scale of one to one; the bust too is authentic. The Droeshout engraving was based on the Flower portrait, which the engraver used as a model. The separate steps in the presentation of evidence are conclusive not only when taken altogether, but for the most part also when they are considered individually. In addition, the signs of disease shown in the images offer unambiguous proof of the identity of the persons represented. They show how the painters, plaster moulders and sculptors of the seventeenth century must have strived to make their work accurate and true-to-life. The truth to life of the Chandos and Flower portraits and of the Davenant bust, and the truth to nature of the death mask, is further underpinned by the fact that the same pathological manifestations are still extant in all of them, at different stages of development and in different stages of preservation. Moreover, when suitably enlarged the skin structure of the deceased Shakespeare becomes visible on the death mask, and this, in conjunction with the proof of identity, shows that the plaster cast really did derive from the mould taken from the poet’s face after death. The organic substance still extant on the mask in the form of individual hairs is a further very decisive and unmistakable sign of its genuineness – as are the “ruins” or craters of a once trilobate protuberance in the nasal corner of the left eye, revealed by spatial-digital measurement. The funerary bust of Shakespeare must also once have possessed this sign of illness, because it appears on a marble copy derived from the bust.

*****

Hammerschmidt-Hummel presented the proof of authenticity for the Chandos portrait, the Flower portrait and the Darmstadt Shakespeare death mask in June 1995 at a press conference of the City of Darmstadt (owner of the death mask), and published her illustrated lecture in the Shakespeare-Jahrbuch (1996). A summary appeared in Anglistik. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Anglistenverbandes (März 1996). There she published two further studies with new research results on the authentic likenesses of Shakespeare (Sept. 1996 and März 1998). In 2000 her paper entitled, “What did Shakespeare Look Like? Authentic Portraits and the Death Mask. Methods and Results of the Tests of Authenticity”, appeared in the American yearbook Symbolism. An International Annual of Critical Aesthetics.

In 2006, following ten years of research in Germany and abroad, she presented the book Die authentischen Gesichtszüge William Shakespeares. Die Totenmaske des Dichters und Bildnisse aus drei Lebensabschnitten. Link auf die Untermenüpunkte des entsprechenden Buches legen. This volume, with ca. 130 illustrations, was sponsored by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (German Research Council). In the same year it appeared in an English translation, published by Chaucer Press in London: The True Face of William Shakespeare. The Poet’s Death Mask and Likenesses from Three Periods of His Life.

The book contains the explanation of the interdisciplinary research methods adopted and the positive results of the identity and authenticity tests of four Shakespeare likenesses, the description of the pathological findings as established in expert medical reports, and a series of new insights regarding the discovery, ownership, history, authorship, and dating of the paintings examined. As will be shown in conclusion, these new findings cohere convincingly with known and new knowledge of the biography of William Shakespeare and provide information about the possible causes of death of the poet.

The public presentation of the German original edition took place on 22 February 2006 at a press conference of the City of Darmstadt in collaboration with the Hesse Land and University Library, Darmstadt. At the same time the English publisher Chaucer Press, London, issued a press release. Extensive coverage appeared in the media.

*****

After Dr. Tarnya Cooper, a Curator at the London National Portrait Gallery (NPG), had questioned the genuineness of the Flower portrait, Hammerschmidt-Hummel, in collaboration with eight international experts, provided additional proof to show that the Flower portrait which arrived at the Stratford Gallery in 1895, was first x-rayed in 1966, fundamentally restored in 1979, and examined by the author in 1996 in Stratford (in the presence of Brian Glover, then Director of the Royal Shakespeare Company Collection), was indeed the authentic portrait of Shakespeare, painted from life. The names of the experts involved are: Reinhardt Altmann, former expert at the German Federal Bureau of Criminal Investigation (BKA = CID or FBI), Wiesbaden; Professor Dr. Wolfgang Speyer, University of Salzburg, Expert on Old Masters at the Dorotheum, Salzburg; Helmut E. Zitzwitz, Conservator, former owner of the Hudson River Gallery & Conservators, Yonkers, New York; Dr. Thomas Merriam, Anglo-American Shakespeare Researcher, Basingstoke, England; Professor Dr. Jost Metz, former Director of the Dermatological Clinic of the Horst Schmidt Clinics, Wiesbaden; Professor Dr. Volker Menges, former Head of the Central Department for Radiology, Computer and Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Nuclear Medicine and Ultrasound Diagnostics at the Theresa Hospital, Mannheim, an Academic Teaching Hospital at the University of Heidelberg; Dr. Eberhard Nikitsch, Inscription Expert at the Academy of Sciences and Literature, Mainz; Dr. Eva Brachert, Painting Restorer at the State Museum, Mainz.

In addition, on the basis of the available expert reports, the author was able to prove that it was not the original painting (missing since c. 1999) but rather two different copies which were used for examination at the London National Portrait Gallery. See also: “Not authentic images of Shakespeare”.

Hammerschmidt-Hummel published some of her findings in a press release back in 2007, which unleashed a debate in the media. (see “Debate” - “Press Release - Where is the original Flower Portrait?” The Flower Portrait. Dann auf ‚Press Release – University of Mainz, Germany‘ - English.)

In 2010 she published the book, And the Flower Portrait of William Shakespeare is Genuine After All. Lastest Investigations Again Prove its Authenticity with 70 illustration on CD-ROM.

It was presented to the public on 28 September 2010 in the Philosophicum of the University of Mainz. See also the announcement “Latest Findings in the Field of Shakespeare Research” (English translation of the German text: “Neueste Ergebnisse auf dem Gebiet der Shakespeare-Forschung”, published in: Damals (5. Januar 2011), as well as the arrangement of details from the original painting and its two copies below.

|

Left: The Flower portrait (original), detail, top left: inscription, date and crack. The original painting, which has been missing since 1999, as examined by the author in 1996 at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon – in the presence of Brian Glover, Director of the Royal Shakespeare Company Collection in Stratford. For publication purposes, Glover provided her with a high-resolution ectachrome. As discernible here, the edges of the 500-year-old original panel are fragile and cracked and have been broken or chipped away in places. In the region of the inscription (up to the upper edge) there is a clear crack.

Right top: Undeclared copy of the Flower portrait. Still image with time code from the BBC film, “The Flower Portrait” (2005). One can see a very robust wooden panel, consisting of a wider and a narrower panel glued together. The upper edge and painting surface show no crack. The Anglo-American Shakespeare researcher Thomas Merriam wrote in his review, “A Question of Authenticity” in Religion and the Arts (2009), the upper edge shows “solid, light-coloured, untreated wood” and appears to be out of “freshly cut wood without suggestions of aging or crumbling”.

Right bottom: The upper edge of another, undeclared copy of the Flower portrait. This painting was examined, measured, and photographed by the author in 2007 in the depository of the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford - in the presence of Curator David Howells, Prof. Alan Bance, University of Southampton, Mrs. Sandra Bance and Dr.-Ing. Christoph Hummel. The upper edge also appears robust and not at all crumbling. It also lacks a crack or broken off pieces. In the place where the wide panel had been glued together with a somewhat narrower one, one can see a slight step. This copy differs greatly from the original, but also quite distinctly from the first copy.

PUBLICATIONS

Printed publications

Books

And the Flower Portrait of William Shakespeare is Genuine After All. Latest Investigations Again Prove its Authenticity / Und das Flower-Porträt von William Shakespeare ist doch echt. Neueste Untersuchungen beweisen erneut seine Authentizität

Publications in the course of work on the project (1995-2005) William Shakespeare: Die authentischen Bildnisse

PDF-Dokument

|

The Research Results of Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel as Mirrored in the Reviews and Comments of Scholars and Scientific Journalists |

Articles

"What did Shakespeare Look Like? Authentic Portraits and the Death Mask. Methods and Results of the Tests of Authenticity." Symbolism. An International Journal of Critical Aesthetics 1 (New York, 2000), 1 - 41

“Shakespeares Totenmaske und die Shakespeare-Bildnisse 'Chandos' und 'Flower'. Zusätzliche Echtheitsnachweise auf der Grundlage eines neuen Fundes” (Shakespeare’s Death Mask and the Chandos and Flower Portraits. Further Proofs of Authenticity on the Basis of New Findings), Anglistik. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Anglistenverbandes (März, 1998), 101-115

“Neuer Beweis für die Echtheit des Flower-porträts und der Darmstädter Shakespeare-Totenmaske. Ein übereinstimmendes Krankheitssymptom im linken Stirnbereich von Gemälde and Gipsabguss” (New Proof of the Authenticity of the Flower Portrait and the Darmstadt Shakespeare Death Mask. A Matching Sign of Disease in the Left Forehead Area on the Painting and Plaster Cast), Anglistik. Mitteilungen des Verbandes Deutscher Anglisten (September 1996), 115-136

“Ist die Darmstädter Shakespeare-Totenmaske echt?” (Is the Darmstadt Death Mask Genuine?), Shakespeare Jahrbuch 132 (1996), 58-74 (slightly shortened speech held at the press conference in Darmstadt, 22 June 1995)

Interviews

“Die authentischen Gesichtszüge William Shakespeares”, Marie-Christine Werner im Gespräch mit Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel (The True Face of William Shakespeare, Marie-Christine Werner in Discussion with Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel), “Journal aus Rheinland-Pfalz”, SWR2 (8. August 2006)

“Interview mit Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel am 9. Mai 2006 anlässlich der Veröffentlichung ihres Buches Die authentischen Gesichtszüge William Shakespeares. Die Totenmaske des Dichters und Bildnisse aus drei Lebensabschnitten” (Interview with Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel on 9 May 2006 on the occasion of the publication of her book, The True Face of William Shakespeare. The Poet’s Death Mask and Likenesses from Three Periods of His Life)

“Was hat die moderne Radiologie mit dem Renaissance-Dichter William Shakespeare zu tun?” - Brigitta M. Mazanec - Am Tisch mit Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel, Shakespeare-Expertin (What does modern radiology have to do with the Renassance poet William Shakespeare? - Brigitta M. Mazanec - A Conversation with Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel, Shakespeare Expert), Hr2 Doppelkopf (28. April 2006) Link auf Hauptmenüpunkt ‚Radio Broadcasts‘ legen “Neue Shakespeare-Büste”, Anja Höfer im Gespräch mit Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel, “Journal am Mittag” (New Shakespeare Busts, Anja Höfer in Discussion with Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel), SWR2 (27. Februar 2006)

“Die Totenmaske eines Dichters - wer war William Shakespeare wirklich?”, Markus Philipp im Gespräch mit Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel und Kurt Otten (The Death Mask of a Poet – Who was William Shakespeare really? Markus Philipp in discussion with Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel and Kurt Otten), “Das Thema”, rheinmaintv (24. April 2006)

“Images ‘show face of Shakespeare’”, BBC NEWS: Professor Hammerschmidt-Hummel interview on Today, BBC RADIO 4 (23 February 2006) - news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/4742716.stm

“William Shakespeare. Buchvorstellung im Magistratssaal der Stadt Darmstadt am 22. Februar 2006” (William Shakespeare. Book Presentation in the City Council Room of the City of Darmstadt) von Ivonne Büttner, Prometheus - Das Wissenschaftsfernsehen für Baden-Württemberg (23. Februar 2006)

Ev Schmidt, “Kriminalbeamte und Wissenschaftler beweisen Authentizität einer Shakespeare-Büste. Gespräch mit der Shakespeare-Forscherin Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel von der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz” (Ev Schmidt, Criminal Investigation Experts and Scientists Prove Authenticity of a Shakespeare Bust. Discussion with Shakespeare Researcher Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel from the Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz), Kulturradio am Vormittag – Wissen, RBB (18. Oktober 2005)

* Further information: The illustrations in this section are, unless otherwise specified, taken from: H. Hammerschmidt-Hummel, The True Face of William Shakespeare. The Poet’s Death Mask and Likenesses from Three Periods of His Life. London: Chaucer Press, 2006. The images are protected by copyright and may not be used without the prior consent of the copyright holders.

** The summary was taken from the same volume, ibid., p. 80.